I had been excited for Marty Supreme for over a month before I finally saw the movie. It all started with this dumb viral zoom skit. Digging further into advance screening sentiments, I had a biased prior belief that this movie, capitalized as Dream Big, was way darker than it was commercially sold as; that this was beyond American dream, maybe about some money-hungry sociopath who’s chasing their aims at the cost of sacrificing and scamming their close ones, much like the whiplash plot in spirit, or uncut gems.

Turns out it wasn’t super overwhelming. It was a good movie. Fantastic cinema, quite frankly. It was revealed as merely a Safdie-esque frenetic story, where perhaps the only unsettling parts were the honey licking scene and Kevin O’Leary confessing that he’s a century-old vampire (which was almost funny and I’d love to believe). My eyes grew somewhat misty at the end of the film.

Some of Josh Safdie’s interview claims might offer a bit clue for the story. He wrote an alternative version of Marty shown in the 1980s (glad it was cut), watching a Tears for Fears concert with his grand daughter, listening to the lyrics of ‘Everybody Wants to Rule the World,’ and reflecting on his youth. So the story was told more so as a resuscitated memory from the lens of a 50s person, however, channelling from the 80s, speculating back on the New York hustle of the boomer era from three decades away. Josh was born in 1984, but his comment on this does feel very personal:

President Reagan was nostalgically in that first era of postmodernism, actively trying to recall the ‘50s. In the face of defeat from Vietnam, culture was really just starting to redo itself in the vein of the ‘50s. You saw it in style. You saw it in movies. ‘Back to the Future’ is literally going back to the ‘50s. But on a very simple level, what happens when you do that is the past starts to feel like it’s haunting the future, and the future feels like it’s haunting the past.

The vertigo was injected a lot through a bunch of 80s pop and Daniel Lopatin’s synth-wave and experimental electronic sounds. You hear those quick transient echoes when Marty Mouser jumps through the fire escape, when he plays table tennis, and when he stumbled away in the cab with Wally from the gas station, leaving a wall of flames and the group of bowling alley hippies in the dust, while watching the dog Moses from the rear window, galloping through the haze. There’s grief in those moments, and the propelling urge of marching forward into a future of some neon twillight. We already know the American dream was shattered by the 80s with the return of the Vietnam war veterans, the collapse of Bretton-Woods, the de-industrialization and the cold war anxiety and so on and so forth. That perpetuating anxiety is what we’ve seen and kept seeing nowadays, anywhere and everywhere, from Reaganomics to MAGA to all the “bring back manufacturing/technology/capital” rehtoric, for instance.

What’s confusing is that it does bring some uncomfortable empathy out of me. You see this wide-eyed, determined Jewish asshole living his life in total chaos on top of everyone around him; you see this unresting nature, rooted whether from the mundane crowd in lower east side of Manhattan or from his nomadic ancient history; you see this poignant, Don Quixote type of optimism, which is what lured him into cascading series of crises, essentially cursed by a simulation that is beyond his time. Sponge paddles were literally introduced to table tennis in 1952 by the Japanese, so his crashing out felt almost legitimate, in a way that you imagine had he been born a couple of years later, he might have mastered the new technique that came along with it.

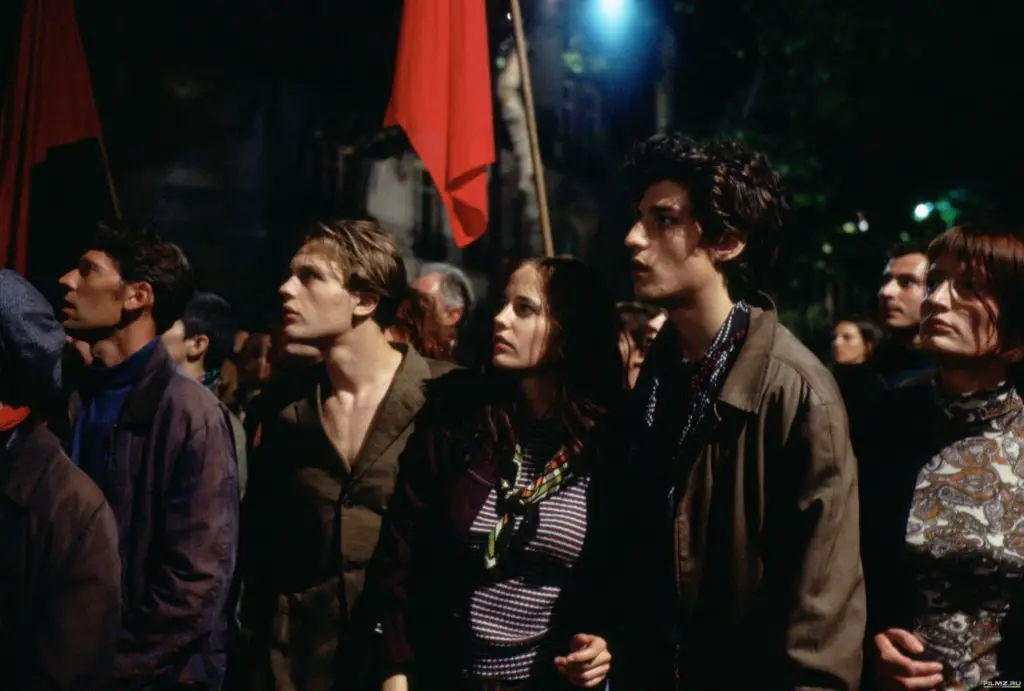

I’m positive Josh Safdie never overthought the final match, though it’s hard for some not to blame the victory for hurting the national pride of Japan. I mean, it’s also presumptuous to bet that Marty would crush Endo. In hindsight, Japan did take a huge economic leap, with its younger generation pondering individual alienation; the revival mirrored the US booming with an approximately 10-year lag. By the end of the ‘80s, Murakami had been writing about self-alienated westernized men from the era of the 1968 student riots, living in Tokyo or somewhere, drinking whisky, mumbling some deep unnameable sadness while listening to Jazz.

The Japanese bubble crashed in the 90s–the bubble trope has been ubiquitous anyway–but Japan did enter the long resignation with its aging population and the emergence of “social recluses”; while the US slipped into another loop, which, needless to get into, was no doubt the core Millennial memory that bred the story. Stripping away the commercial framing and Timothee Chalamet’s comedic greatness chasing persona, the flashbacks of some NYC film bro running around are pretty vivid; as if you can hear those cocky cunning but shockingly contagious dialogues from this guy, in between those wild low-budget indie projects, exhausting his brain to make it through; and you see the image of his personal reconciliation with marriage and parenthood from his ultra-personal expression: “he ends up fathering his dream”.

Coincidentally, the Chinese had a compressed version of the “dream of granduer” booming in the early 2000s; it happened so fast that the mirage still lingers in many ways. A common feature in societies like that is the frantic, over-selling confidence from Marty Mouser was secretly rewarded in those early days of the age. We saw Jack Ma advertising his “AI (爱) is love” and all those bullshitting successology sellers (well on the other side you had Elizabeth Holmes etc.). Yet all of a sudden, we find ourselves living in such a difficult time where we seem to have been skeptical of the reward process for decades, (come on everybody loves nonchalantness).

I tend to believe that the raw, carnal love and maybe the nearly pathological internal drive are what can help us to transcend those unsettling eras. But it’s also dangerous because you could easily get consumed. Safdie did try to sell some hope here. Marty was on an odyssey to private redemption and homecoming. His sexual entanglement with Rachel and Kay is both transactional and real, and key to forging his acceptance of what we can even argue as mundaneness. There’s a lot of beauty to that, even to the moral complexity. In the end, we do wonder how his kinetic energy keeps him forward.

It’s still ironic looking back at how They promoted this as some sort of bleak winter fire. During the movie, Dion finally reached the breaking point, where he tossed the boxes of Marty Supreme balls out of the window. As they scattered everywhere on the street, the suggestion for a rain of Ping-Pong balls in the viral Zoom recording feels even more surreal. I thought that was some really genius shattering.